The snow came, that great revealer, and with it came the elk herds, antelope herds, mule deer herds and the quiet shush of the slumbering winter world. We went out in it with our eyes and hearts wide open.

From our skis, on the first day, we saw a bachelor herd of elk in the sagebrush. To run away from us, they first ran towards us, traveling on the old, trampled trail they share with the deer and pronghorn, until they crossed the two track we were skiing — not twenty feet from our rosy, wind bitten faces. Farley was ahead of us and he reared back on his hind quarters and cowered in the snow as they passed. The world then was thrashing and humming with antlers, mild-mannered-testosterone, cold smoke and wild eyes.

We saw the way the snow had pushed the birds down low in the canyons. We saw how desperately they were feeding on spring moss when we inspected their crops in the evening, before dinner. We watched the fit survive and the unfit die. We saw how the Hungarian partridge fared best of all, more adapted to cold and deep snow. We saw the bony breast of the chukar, the fatigue of the quail who lives there on the tender threshold of his territory.

Sometimes the lives of the unfit were taken by our own guns and dogs and we didn’t feel badly about that. So thin were the quail, if we didn’t eat them, the coyotes, hawks or owls would have.

What’s the difference, in the end?

I saw that beautiful shift and sway and cycle of energy, of consuming and being consumed, that has always been and always will be, as far as the stars, and beyond them too.

Another day, while I skied alone, I saw the same herd of elk, the full herd, a herd of what I estimate to be 400 animals. I saw them out in the sage as I skied and they saw me. And to run away from me, they ran toward me again, on that same old highway the ungulates have been walking this winter, and once more they crossed my two track so close that I could smell the musk of their piss and wildness and fur and see the pupils in their eyes and Tater and I stood in awe and wonder as the snow-muffled thunder of 400 elk crossing took our breath from us. We waited while they all crossed our trail and at first I struggled to free myself from my gun and pack so I could recover my camera and photograph it and then the struggle began to take away from the holiness of the moment and I eventually allowed myself to simply sit there, squatted in the snow, hunched over my skis, arms wrapped around a hysterical dog as the elk passed us by. It occurred to me that everyone has been using the phrase “wild and free” lately and they don’t know what the heck they are talking about. They don’t know.

We skied down the hill from there into slightly lower country and as we came around the corner of a coulee, we came upon a huge bull elk, bedded down. He looked over his shoulder at us, his branching antlers cutting at the sky, slowly stood, jiggled his balls about and then trotted off through the sage.

I felt my human heart pounding.

I saw the way the mice zig zag between the sagebrush, darting between cover, trying to avoid the omnipotence of the hawks. I saw their tiny, pouncing, dashing footprints in the snow and understood their clever survivorship by the meaning of their tracks.

I saw a herd of pronghorn that was so big. So big. The biggest I have seen. Their bodies were electric in the sage, white rumped, bounding.

I saw the hard work and broad hearts and bright eyes of my dogs. I saw them live their instincts. I let them do the work they were bred for. I watched them follow their noses. I believed in them. I had faith in their abilities. I trusted in their body language. I brought home birds for dinner.

I shot so well. I outshot Robert. It was a miracle.

I shot my first, clean double on Hungarian partridge and we celebrated with a cold, numb-lip kiss in the field while Farley fetched them up for me and placed them in my hands.

We skied by headlamp. We saw the stars. We loved the moon. We drove home while sipping hot tea from a thermos.

I saw a patch of bloody snow. I found the tail of a jack rabbit there. Just the tail. Soft and perfect — kitten grey on one side and ink black on the other. I pulled off my mitten, stroked the fur for a moment, then put it in my coat pocket to take home. I wondered if the kill belonged to hawk or owl. I’ll never know.

We hunted the place of hares. I have never seen such a thing in my life. When I looked up to the sagebrush covered hills above the creek and allowed my eyes to adjust, I could see jack rabbits moving across the snow like a plague — twenty rabbits, forty rabbits, sixty rabbits. They seemed to multiply before my eyes; double with each blink. All around me, I could see where they had stood beneath the sage on their hind legs and nibbled as far as they could reach up the branches. Beneath the sagebrush lay piles of mowed leaves, downy as feathers on the crust of the snow.

There were so many hares they had made highways, packed the snow beneath their long, broad feet, so that the trails held me up as I walked. As soon as I stepped off a rabbit track, I fell post-hole deep into powder.

We saw a parliament of owls. Oh, there must have been thirteen. I tried to count but they were whizzing around like mad and flapping those wide wings attached to weightless bodies. They had been roosting together in a tall clump of sage and as our quail hunt disrupted them, they rose up, beating at the thin air and we, so deaf to the drumming of their delicate feathers, marveled at their silent flight. I have never seen a parliament of owls like that. So close to me. So acrobatic in flight.

Later that night, on the drive home, I saw a great horned owl in a wind belt on the edge of a ranch. I called out “owl” as I pointed at it, but by then we were so desensitized to wild beauty it almost seemed ho-hum. Almost. No. Not quite.

No.

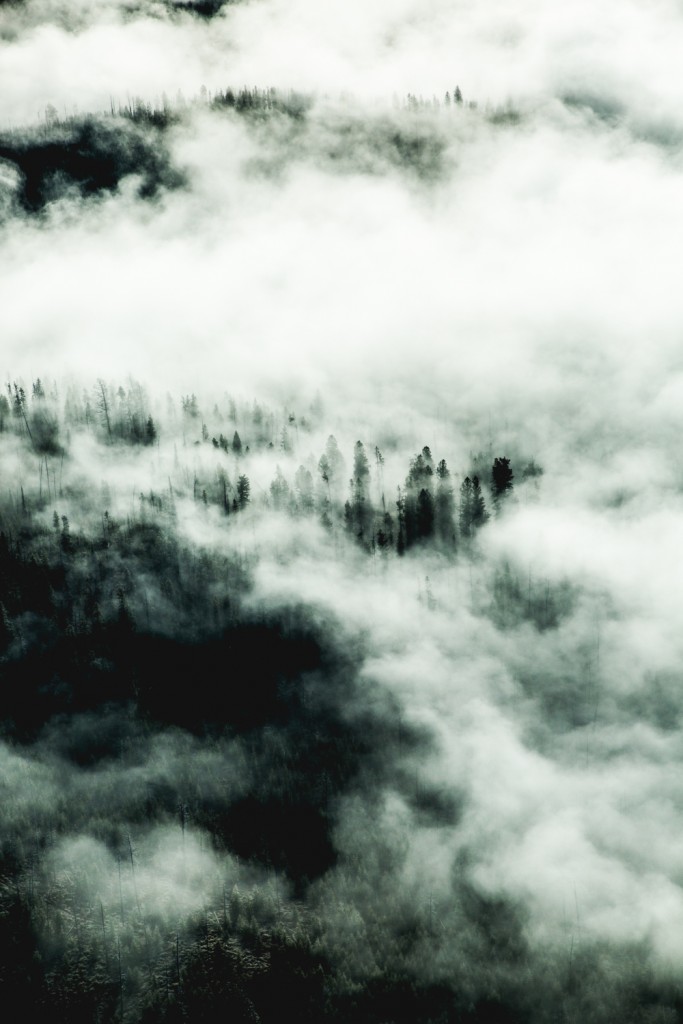

As we hunted, we heard a pack of wolves howling. The wolves go where the elk go. The elk are so low now the herds can be seen from the interstate that passes between Boise and Pocatello. I wish I could wake up one morning and see a wolf, riverside here, sipping from the turquoise-green as it rushes by.

We were looking for pheasant and quail but instead, we found porcupines. One was in a willow, high up in the skinny branches, shredding bark and slowly nibbling his dinner down. The porcupine is the North American version of the sloth but not as slow. I will testify to the fact since we saw a second descending the slope across the creek from us and he was covering ground at a porcupine-gallop. For a moment, I felt a little fear.

Naturally, I was compelled to do some porcupine research and the most important thing I discovered is this, “…porcupettes are precocious at birth.” Then, I laid there, crammed on our loveseat and covered in a cat, looking at Google images of porcupines and hollering at Robert each time I found a photo that was especially cute.

This is all to say that this winter, so far, has been incredible. Each time I step outside it’s as though I have entered a biology classroom and I’m gifted with all the truest teaching I have ever craved on the topic of the wild world around me. I would like to think that if I wasn’t hunting, I would still go out there, I would need no reason to go. But to have the reason to go out there to get my food is one of the greatest reasons of all and I have learned so much about my quarry, about my dogs, about my man and me, about being human, about being an animal, about how to move and think and feel, about how to sense, that I think I’m past the point of no return.

There’s no going back now.

The sun has set on any chance that I might have to be tamed in this life.